So, as happens in writing, sometimes you spend a lot of time and effort researching and writing about a thing before a change in direction requires you to abandon hours or days of work. When my current book project pivoted away from the more historical and academic framing I’d originally started with, about 70 pages of material ended up on the cutting room floor. In general, that’s not a big issue — I have a google drive with hundreds of thousands of words of prose that will never see the light of day, not because the writing is bad, but simple because things change and sometimes ideas get left behind.

For this project, though, one of the things that got left behind wasn’t an idea — it was a person. Namely, Frank Rosenblatt. In my previous work, Frank was given a much more substantial role in the narrative, both because I find his story compelling and because I think his career arc really humanizes things in a way that is rare. Today when we see someone standing in the middle of a media tech frenzy it’s because they chose to be there. They asked for the attention and all that came with it because in the modern media landscape, attention is everything.

But Frank didn’t really choose to be the main character in his technology hype cycle. He wasn’t Edison or Jobs — men who famously used the media’s hunger for fantasy to propel their financial interests. Frank was just a guy who wanted to chase a cool idea, and just happened to be chasing it at a specific time and place where everyone else’s fear and insecurity co-opted him and drove him down a path he was powerless to change.

So, because I think Frank’s story is one worth reading, I’ve decided to share it here as it was originally written, before it had to be distilled down to accommodate the need for other stories to share his space. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

In the summer of 1958, Frank Rosenblatt stood before a wall of cameras and uniformed officers with the bearing of a Cold War hero.

Tall, composed, unmistakably confident, he looked like a man who had stepped out of a recruitment poster and into the vanguard of a technological revolution. This was his moment. The moment where a single scientist could claim the future in front of the world. He stepped to the microphones and announced, simply, that the era of learning machines had, at long last, begun.

The room was thick with the sort of tension reserved for the unveiling of a new weapon in the fight to contain communism. The silence was broken only by the sizzle of flashbulbs.

Behind Rosenblatt sat the Mark I Perceptron. It lurked on the table like some unknown animal — wires coiled across its frame, relays clicking softly as though warming up for its cue. The Navy officers stood rigid in their dress whites, an institutional endorsement no one in the field had ever enjoyed. Reporters scribbled notes furiously, convinced they were witnessing a step into a brave new world — the dawn of machine intelligence.

Rosenblatt, basking in the weight of the moment, carried himself like a man who believed every word he’d just spoken. Perhaps he had. For a brief instant, it truly seemed as though the future had arrived.

Frank was remarkably calm considering how quickly he had gone from relative anonymity to national recognition. Less than a year earlier, he could have been found in an unremarkable office in a wing of the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, surrounded by disposable coffee cups, half-eaten sandwiches, and a pile of psychology journals. He was sorting through notes, sketches, and graphs, trying to piece together an idea that had stubbornly eluded him for months.

Even before that, there was little reason to believe Frank was destined for greatness. Born and raised in a middle-class Jewish family in New York, he had attended the Bronx High School of Science — a well-known magnet for intellectually ambitious kids, but hardly the kind of private institution designed to usher future elites into prominence. His work as an undergraduate in psychology earned him the respect of his classmates, and throughout his graduate years he was seen as bright and affable, but not particularly visionary.

If two qualities set Frank apart in those early years, they were his willingness to cross disciplinary boundaries and his persistent enthusiasm — enthusiasm that sometimes made senior academics uncomfortable. To some, he came across as a man so passionate about his ideas that it felt as if he were trying to sell you something. No one doubted his conviction. But that conviction manifested, more often than not, as what people today might call hype.

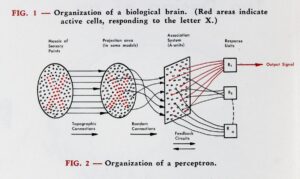

But on that autumn night in 1957, Frank’s concern was the idea he still couldn’t quite bring into focus. He’d studied the work McCulloch and Pitts had published fourteen years earlier — the artificial neuron as a logical device — and was struck by the audacity of it: a simple mechanical process, with no understanding of its own inputs or outputs, could nonetheless carry out operations of logic. But he also knew logic wasn’t enough.

The behaviorists had insisted that learning was nothing more than stimulus and response: a child touches a hot stove and recoils; a rat presses a lever and finds the pattern that delivers food. Cognitive scientists, reacting against that reduction, had begun to frame intelligence as a system of rules — some internal grammar of thought that, if mapped and formalized, could be reproduced in a machine. Both views had mechanical elegance, but neither felt alive. If learning was real — if it had a physical basis — it had to be distributed rather than symbolic. It had to emerge from simple parts interacting, not from instructions handed down from above. Frank flipped through another notebook, reexamining old sketches. They still felt wrong: too static, too brittle: like diagrams waiting for a spark that never came.

Then, sometime around midnight, he drew a new version. It wasn’t deliberate; the pencil moved as if tracing a thought he’d been circling for weeks. Inputs leading into a unit. Weights adjusting with each success or failure. A mechanism that strengthened when it guessed correctly and weakened when it didn’t. A system not programmed but shaped—molded by encounters with the world. He stared at the page. It wasn’t a breakthrough, not yet. But for the first time, the sketch didn’t feel inert. It looked, in some small way, like the beginnings of something that could learn.

What Frank had begun to figure out was something that would later become one of the foundational ideas behind modern machine learning: intelligence doesn’t emerge from rules. It emerges from adjustment. Each experience nudges the system — strengthening some connections, weakening others—until the machine gradually settles into patterns that reflect the data it has absorbed. Learning, in other words, wasn’t a matter of telling a machine what to do. It was a matter of letting it change itself. Rosenblatt didn’t yet have the mathematics to prove it or the hardware to test it, but he had sensed the essential truth that would underlie every neural network for the next sixty years.

Frank didn’t have the mathematics to prove his idea, or the hardware to test it, but he had something just as powerful: momentum. He saw the outline of a possibility and did what men like Frank often do when they glimpse a breakthrough that isn’t yet real. He moved. Fast.

The sketches weren’t finished, the assumptions weren’t validated, and the gaps were wide enough to drive a truck through, but none of that seemed to bother him. If you’re convinced you’ve stumbled onto a way to reshape the world, hesitation feels almost irresponsible. The big picture is obvious; the details, you tell yourself, will sort themselves out.

He started talking about the idea — first to colleagues in psychology, then to the engineers down the hall at the Aeronautical Laboratory, and finally to anyone who would sit still long enough to hear the pitch. The reaction was uneven: some thought it was clever, some thought it was confused, and a few thought it bordered on quackery. But Frank’s enthusiasm and authenticity were infectious. People found themselves nodding along even when they weren’t entirely sure what they were nodding to. Here was a man promising a revolutionary new technology, rooted in cutting-edge science. And few, if any, understood that science well enough to push back with real conviction. Frank was smart, handsome, likable — and, besides, would a man with his credentials really bet so completely on an idea he privately doubted?

In an era when the military was hungry for systems that could detect patterns, adapt to uncertainty, and make decisions faster than any human operator, his idea didn’t sound far-fetched. It sounded useful. It sounded like exactly the kind of thinking the country needed to stay ahead in the race for global power. It sounded like an idea only possible in America.

Within months, word had made its way into the right offices. What had begun as a late-night sketch was suddenly a project with funding, expectations, and its own small orbit of attention.

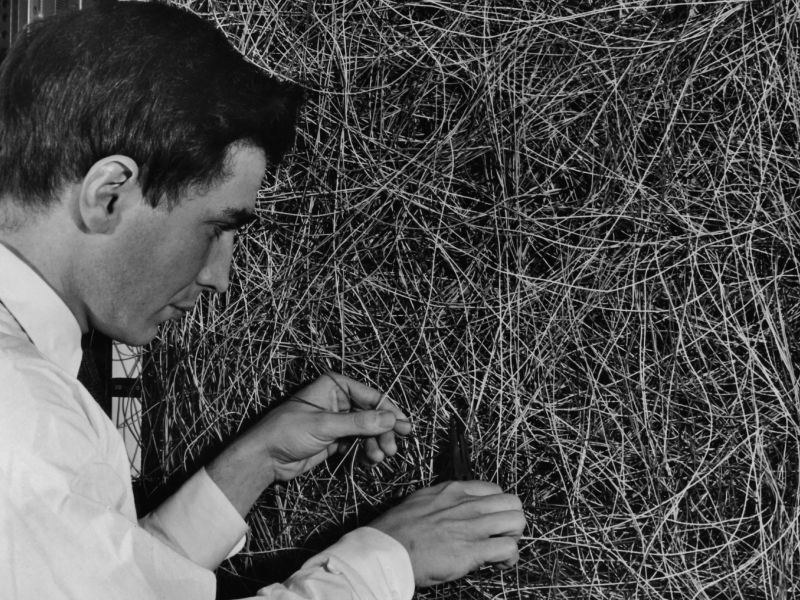

The funding came quickly, and with it came the need to build something tangible, something that could prove the idea was more than an attractive metaphor. The Aeronautical Laboratory assigned him a small team of engineers and technicians, men more comfortable with radar assemblies and flight-control hardware than with experimental psychology. Together they began assembling the machine that would become the Mark I Perceptron. It was an odd hybrid from the start: part laboratory apparatus, part improvisation, part technological wishful thinking. There were motors scavenged from surplus equipment, hand-soldered relays, and a thicket of wires that grew denser with every revision. No one involved had built anything like it before.

Frank was everywhere at once: at the chalkboard sketching revised diagrams, at the workbench soldering connections himself, at a desk typing proposals for additional support. His enthusiasm filled the space as completely as the machine’s wiring did, and for a time the team seemed to feed on it. Engineers who had initially dismissed the project as eccentric found themselves captivated by the challenge of making a machine that didn’t just compute, but learned. Each day brought small adjustments and unexpected setbacks, but progress was visible in the slow, uneven flicker of the system coming to life.

The machine was crude, fragile, and temperamental, but it worked—at least in the limited sense that Frank needed it to. It could take simple visual patterns as input and, after repeated exposures, begin to distinguish one from another. It was not intelligence, not even close, but it moved differently than the logical circuits everyone was used to. It changed itself. And in the fevered imagination of a nation chasing technological supremacy, that single feature was enough to make the project feel like the opening act of something much, much larger.

The Office of Naval Research had taken a keen interest in Rosenblatt’s project from the beginning, but by June their curiosity had hardened into commitment. They authorized a formal demonstration in Washington, announced new funding, and signaled their intent to build a larger, faster, more capable version of the machine. The number that appeared in the paperwork — over a million dollars earmarked for future perceptron research — was staggering for the era. It placed the project not alongside academic curiosities but alongside missile guidance, radar systems, and classified defense technologies.

The first public demonstration of the Perceptron was set for July 7th, 1958. Frank and his team arrived the night before, carrying a heavy box of punch cards wrapped against the weather. Washington was hot and wet that night — thick July air, bursts of rain, and occassional far off thunder that suggested a storm was raging out of sight, beyond the horizon. They were here to reveal to the world a machine that could learn, and the unease in the air felt like a warning not to look too closely at how fragile the whole enterprise might be.

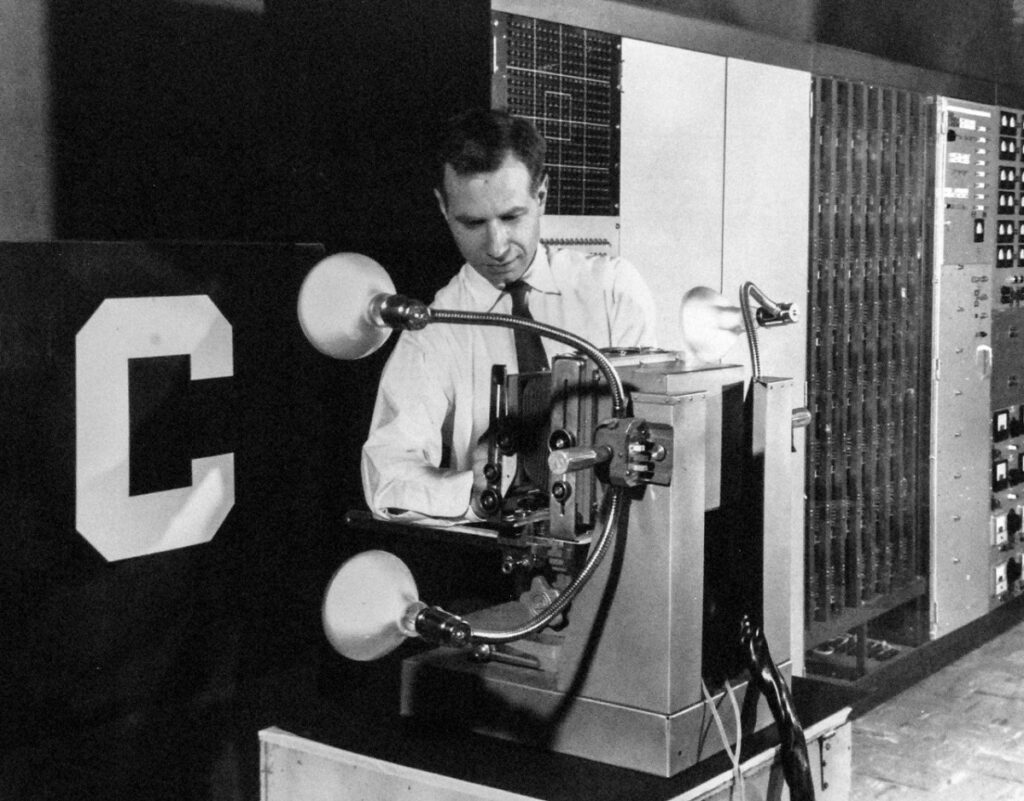

The demonstration took place in a modern federal building that housed the U.S. Weather Bureau. The Perceptron would be run not on their own prototype (which was too delicate to travel), but on an IBM 704 mainframe: a five-ton digital machine that relied on magnetic tape reels and punch cards to guide its operations. The tape containing the program had been shipped by courier earlier in the week. The punch cards carrying the test patterns, however, the team had insisted on bringing themselves.

For the Navy, the absence of the physical machine hardly mattered. The institution wanted the symbolism: an American system that could adapt, classify, and learn—something that might, in the eyes of Pentagon optimists, outmaneuver Soviet systems one day. For those purposes, the simulation was plenty. All anyone needed to believe was that the underlying principle worked.

Once the room had filled with reporters and Navy brass, Rosenblatt walked them through the basics. The Perceptron wasn’t a conventional computer at all, he explained, but a network — one that adjusted its internal weights through repeated exposure to patterns, improving with each trial. The simulation behaved as expected. The tests were simple, even repetitive, but they landed. Enough to make the room lean forward. Enough to spark the sense that something genuinely new was happening.

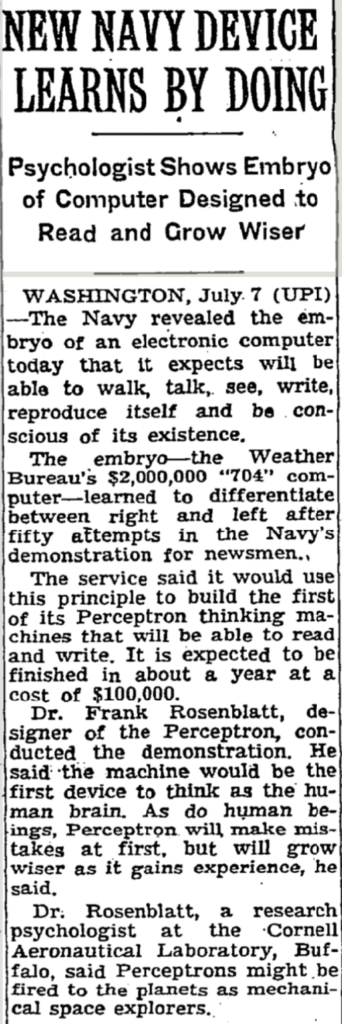

On the morning of July 8th, the New York Times published a prominently placed story about the demonstration. The headline read: NEW NAVY DEVICE LEARNS BY DOING: Psychologist Shows Embryo of Computer Designed to Read and Grow Wiser. The article opened with the breathless tone of a pulp science-fiction serial:

“WASHINGTON, July 7 (UPI) — The Navy revealed the embryo of a computer today that it expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, and be conscious of its existence.”

“The machine… will be able to read and write. It is expected to be ready in about a year at a cost of $100,000.”

The reporter credited Rosenblatt with a slew of extraordinary claims, among them:

- “The machine will be the first to think like the human brain.”

- “Perceptrons might be fired at planets as mechanical space explorers.”

- “Later Perceptrons will recognize people and call out their names, and instantly translate speech into other languages.”

- “In principle it would be possible to build brains that reproduce themselves on an assembly line and are conscious of their existence.”

It’s impossible now to determine which of these claims Rosenblatt actually made and which were embellishments by a reporter who may, for all we know, have been accidentally exposed to experimental hallucinogens by a CIA behavioral lab. The late 1950s were, after all, a strange time to be in Washington, D.C.

What we do know is that within weeks, Rosenblatt found himself living in the very moment where our story began —standing before cameras and Navy officers, unveiling a machine the public had already been told would usher in a new era of autonomous, conscious, mechanical beings.

In the months following the July demonstrations, the Perceptron project expanded quickly. The Navy released additional funding. Work began on the larger, more ambitious hardware version that would become the Mark I Perceptron. Rosenblatt published papers, gave talks, and continued refining the theory. For a short time, everything seemed to be accelerating in the right direction.

***

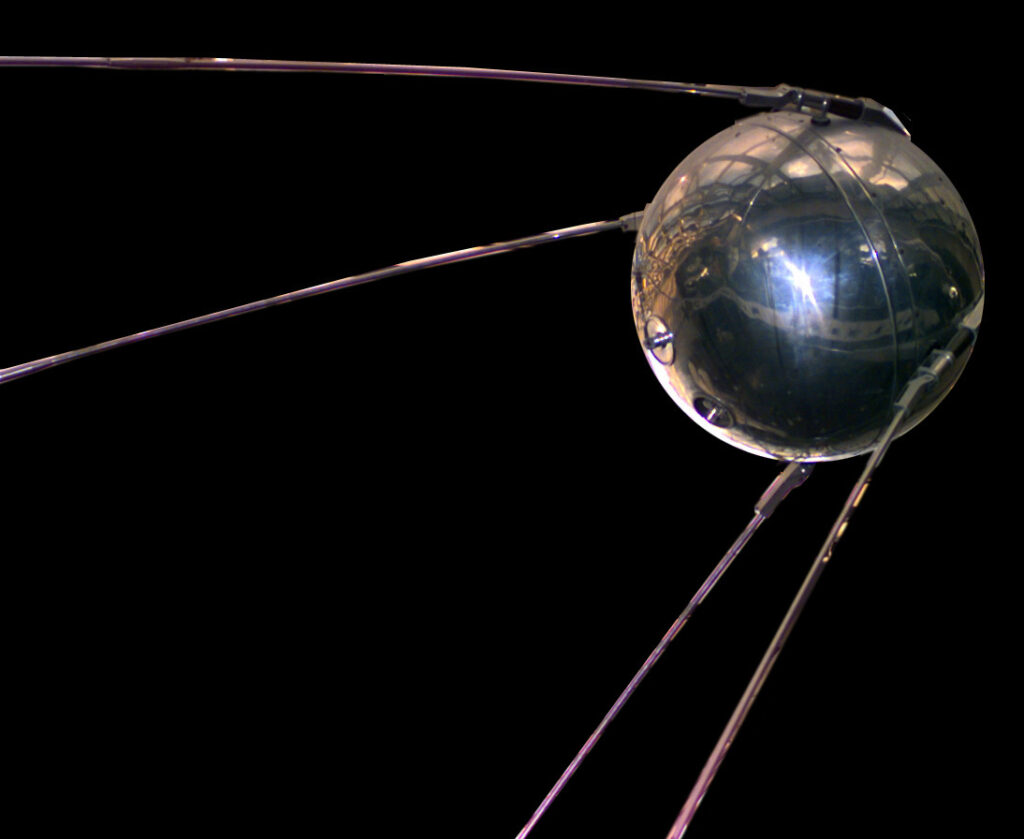

The defining moment in Frank’s story has, until now, stayed off screen. On October 4, 1957, at 7:28 PM, as Frank sat in his office on the edge of revelation, sparks ignited a mixture of liquid oxygen and high-grade kerosene in the engine of a modified R-7 Semyorka rocket half a world away. The Soviet missile carried a 184-pound metal sphere packed with simple instruments and a radio transmitter. As it climbed into the night sky over Kazakhstan, the tension that already defined the Cold War climbed with it.

Sputnik circled the Earth for only ninety-two days before burning up on re-entry. But during those three months, the American public, the media, and the political class collectively began to lose their goddamned minds.

In Washington, panic hit instantly. The Soviets hadn’t just launched a satellite — they’d rewritten the story Americans told themselves about who led the future. Overnight, every wild idea became a potential weapon, every promising young scientist a possible path back to the top. So when whispers surfaced about a charismatic researcher in upstate New York with a machine that could learn, the reaction was predictable.

From a modern vantage point, it would be easy to confuse Rosenblatt with the prototype of the tech evangelist. The cycle of hype surrounding the Perceptron certainly invites the comparison. The media and cultural reaction to potentially groundbreaking new technology feels distinctly familiar. But placing Frank himself in the company of modern day entrepreneurs and grifters would be wrong.

Frank’s flaw wasn’t ego — it was optimism. He never claimed the Perceptron could do more than it actually could. He understood the limits intimately: a single layer could only classify certain kinds of patterns; deeper computation would be needed for anything else. He said as much. It was all in the fine print, the caveats that no one bothered to read.

Frank believed the field would grow into its potential. That new layers, new machinery, and new mathematics would arrive in time. Progress, to him, wasn’t a leap — it was a long march. A steady climb. He trusted the future to meet him halfway.

But Frank didn’t have the future. He barely had years.

Through the early 1960s, the people who had rushed to position his invention as a Cold War miracle quietly began to withdraw once it failed to produce immediate, military-grade results. Support evaporated. Funding shrank. The public grew skeptical. Reporters who once pushed through crowds to hear him now treated him like a punchline — the man who promised a thinking machine and delivered a curiosity.

Colleagues who had admired him started to resent the fame he’d enjoyed, the Navy contracts, the photo spreads. And when the work stalled — when it became clear the hardware simply wasn’t there yet — they told themselves they’d seen it coming.

In 1969, Frank’s one-time friend Marvin Minsky, together with Seymour Papert, published Perceptrons. The critique was devastating not because it was new — Frank had understood the limitations from the start — but because the book hit the field like a verdict. A single-layer Perceptron couldn’t solve certain classes of problems. True. And for many, that sentence was all they needed to close the door.

Single-layer dead end. Case closed. Move on.

Frank knew better. But by then, almost no one was listening.

In his final years, Frank believed himself disgraced. While few in the field actually viewed him through that lens, his failure to actualize his dream would haunt him in the years to come. In 1971, on the occasion of his 43rd birthday, Frank died tragically in a boating accident in the waters of the Chesepeake Bay.

Today, the Perceptron he sketched in 1957 sits at the foundation of the software that powers speech recognition, image classification, natural language systems, trading platforms, autonomous vehicles, and robotic exploration. Historically, the backlash that followed his work marked the beginning of what is now called the First AI Winter — a period when political and financial support collapsed, the media mocked the idea of machine intelligence, and public attention turned elsewhere, toward the comforts of a more familiar past.

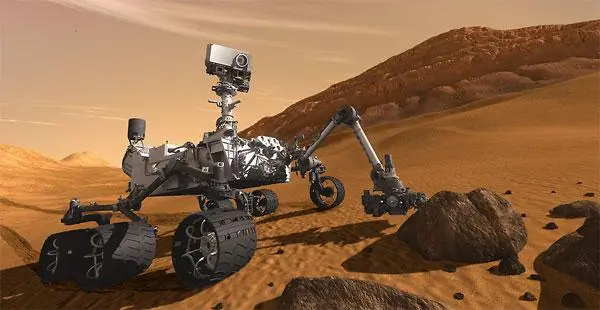

In July 2024, NASA’s Perseverance rover collected samples from a dry riverbed in the Jezero Crater, a stretch of stone patterned like leopard skin. Early analyses suggest potential biosignatures — hints of ancient microbial life. If they hold up, they may tip the balance of evidence in one of the oldest human questions: are we alone in the universe?

Almost no one noticed.

At the heart of the software that guided Perseverance’s search — and at the heart of the instruments that will analyze those samples on Earth — is a neural network architecture descended directly from Rosenblatt’s Perceptron.

- “Perceptrons might be fired at planets as mechanical space explorers…”